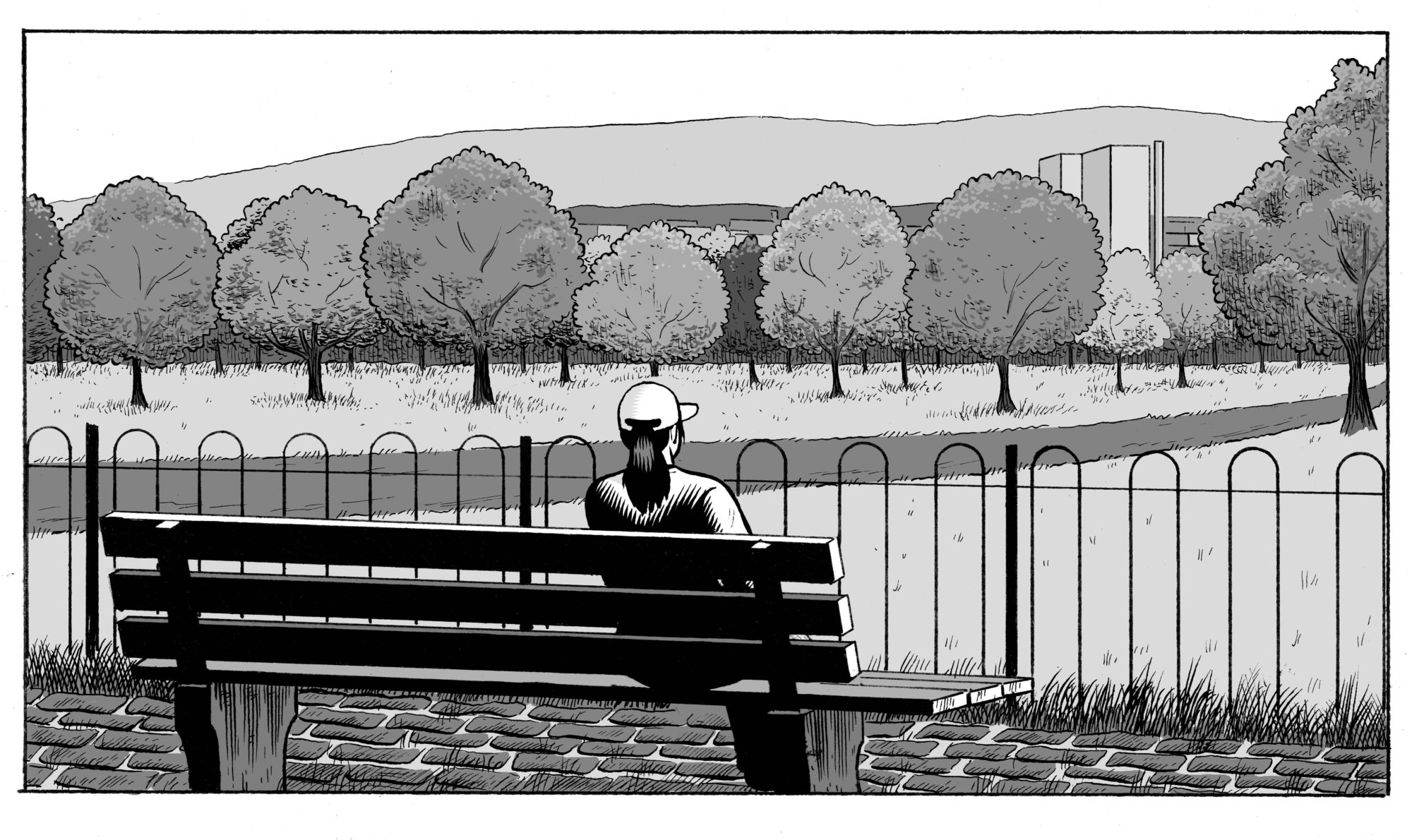

Contributed by Dr Sarah Wishart, EachOther; Still from Excluded © Jon Sack 2021

EachOther is a small human rights journalism charity covering human rights issues in the UK through news articles, features, videos or animations – different formats to engage a wide audience since 2015. We might unpack legal cases or create explainers to examine the world of rights, and we firmly place lived and learned experiences at the heart of all our work.

“I literally just felt so voiceless at the time” – Excluded 2020

In December 2020 we launched our first feature length documentary – ‘Excluded’, which only features the voices and stories of young people with lived and learned experience of exclusion in some way. Some of the young people had been temporarily excluded, some permanently, some had never been excluded – but we felt compelled by Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child to give them all a voice.

I had been looking for a subject on education to work up into a longer film, after being inspired by a Unicef initiative I stumbled upon during our 2018 EHRC commission, ‘FairPlay’. On that project I worked with a number of Unicef’s Rights Respecting schools and handed over the direction of the content to the children to an extent – by enabling them to choose questions that shaped conversations on human rights. Afterwards I started talking to Unicef about the impact of Rights Respecting Schools on older children to see if there was a long-form film there, but on GCSE results day 2018 – I was taken in another direction. When I saw the social media furore that exploded out of ‘Education Not Exclusion’s night-time exertions – I knew I had found the issue we should be telling in a longer form.

But what does it mean to give voice to children and young people that have been silenced?

As Laura Lundy sets out in her seminal 2007 article, ‘Voice is Not Enough’ there must be a process in operation alongside consultation of children and young people. Little did I realise that our process had unwittingly followed the Lundy model.

We created workshops to allow the young people space to talk through what they wanted from the film, what they thought was missing and how they wanted the film constructed. At different stages in the process some young people felt that they were not the right people to participate as they had not been permanently excluded and asked us to find more voices that could speak to those experiences.

We worked to ensure that all different kinds of voices were listened to and were worked with differently. For those that didn’t feel secure speaking directly to camera – even when Covid allowed – we provided them with microphones and worked with their support systems to ensure they were speaking in environments that worked for them. It was also important once we had funding that we paid all the young people that worked with us to ensure that they knew we saw them as collaborators and consultants. We also wanted to keep on consulting throughout the process – not only in the workshops.

We were always aware that the young people who gave voice to the project, particularly those who had left school without qualifications or higher aspirations wouldn’t necessarily see change in their lives from having been involved with the film. Some of those stories, particularly from young people in Scotland (despite the inclusive model embedded in Glasgow being reflective of many of the suggested solutions in ‘Excluded’) – were the most harrowing. Which is why I was so taken aback to hear that the Scottish workshops had seen a significant impact for several of the young people. We were told afterwards from feedback from Meg Thomas Head of Policy at Includem that one young man had felt able to speak about his experiences for the first time without judgment. The young people also talked about how coming together in that way had created a space for empathy in hearing others similar stories, it had shifted their perspectives on their own stories.

“Until they became involved in this project, they had not considered this from a rights perspective. They saw education as something they were made to do rather than something they had a right to access” Meg Thomas

My WhatsApp inbox was flooded the day of the online launch of the film with our young consultants so happy to see their stories being told. We also saw a similar response on social media – with people telling me how important it was for the young people in their care to see their own stories. We are taking this forward with our next project to embed the film in engagement with excluded young people and this time – we will be embedding Lundy’s model in much more deliberate ways.