Please note that the views expressed here represent those of the author and not the Excluded Lives team

By Fran Morgan, Square Peg

Here’s a question for you. What’s the difference between exclusion and persistent absence? As it turns out, very little.

Square Peg refers to ‘barriers to attendance’ which includes both persistent absence, ‘truancy’ and exclusion under that banner. All are a response to unmet need; a form of communication through what is often the only vehicle children have to express distress – behaviour, and withdrawal or anger. It’s also the same fight/flight/flop-drop/fawn responses we see in children exposed to toxic stress (trauma).

We believe that behaviourism (rooted in observing and conditioning mammals to behave in a specific way) is exacerbating these problems in schools. In contrast, our brains are far more highly evolved, with a frontal lobe responsible for reasoning, thought, philosophical thinking, cognition and expressive language. We thrive on connection and interconnectedness, we actively seek it out and need it in place in order to thrive. Relational approaches are far more likely to be successful in reducing persistent absence and the type of challenging behaviour that then leads to exclusion. That means trust, understanding, security, safety, compassion, kindness, relationship – and it’s just as important with families as it is with students.

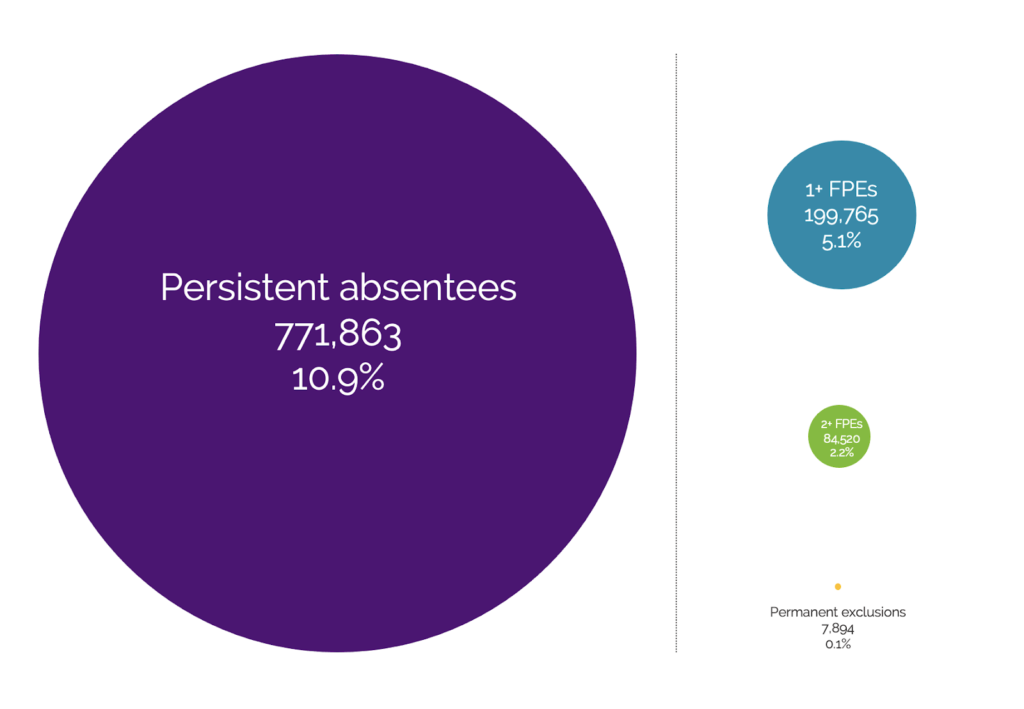

We often cite the statistics, because they are signals of a failing system and they continue to perplex us. The scale of persistent absence compared to exclusion is shocking, and the reason this remains a relatively invisible problem, with little investment given to addressing the causes and finding effective strategies, remains a mystery.

The chart above shows the shocking comparison between students who are excluded and those who become persistent absentees (missing 10% or more of school). Of the 772,000 persistent absentees, 60,000 miss 50% or more of the academic year (there is no data beyond this). 43% of their absences have no formally recorded reason (usually ‘other’), leading to a really dangerous assumption that these children have simply disengaged from education. Some may well have disengaged (and whose fault is that?) but others are simply unable to cope with the pressures of a one-size-fits-all system.

One reason that persistent absence doesn’t command the same attention as exclusion is that these are the pupils who mask at school – staying under the radar, coping as best they can – with the survival mechanism of remaining invisible. They keep going until that’s no longer possible, they’re unable to attend at all, and then they continue to be invisible. Another reason is that extended non-attendance is a complex, multi-faceted problem with no quick fix solutions. Challenging behaviour, on the other hand, must be ‘dealt with’, for safeguarding reasons and so that the learning of others isn’t adversely disrupted.

The response to both types of behaviour may often be punitive; a combination of sanctions for the child, and (for non-attendance) the addition of fines or prosecution for parents. Why? Identifying often complex, multiple and systemic underlying needs, encompassing not only special education, but social/emotional mental health, social care, welfare, physical health, cultural, ethnic and socio-economic needs, and offering appropriate support would be time-consuming and costly. Better then to simply enforce compliance.

So what can be done to address the issue of persistent absence (and to a certain extent exclusion too)?

- A trauma-informed school culture reduces absence and exclusion and there is growing evidence to support this. It must come from the top down, be a whole-school, whole-child philosophy of approach and practice, although individual staff can still develop the knowledge to give themselves agency. Change and impact is still possible, one interaction, one relationship at a time. Relationships with families are as important as relationships with pupils/students. This takes time; the triggers that affect behaviours in children are just as present in their parents. Some will have had a really poor experience of schools themselves, others will be experiencing huge pressures in their own lives which impact on their ability to connect with school and their child’s education. Walking alongside and putting parent voice on an equal footing with professionals is key.

- There is much talk of ‘reasonable adjustments’, but they can be an inconvenience or incompatible with school policy. Let’s face it – quiet children sitting neatly in rows and doing as they’re told is the most cost-effective way to ‘deliver’ education. Sadly, it doesn’t work, so the more flexible schools can be – the more they can adapt their own working practices to meet the needs of individual pupils, offer trauma informed CPD, the more likely they will be to have happier children with reduced stress, all willing and able to learn. Not only that, those children will be less likely to carry mental health challenges into adulthood, develop health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes or die prematurely; and they will be more likely to have stable, positive relationships, hold down a job, and be resilient compassionate parents themselves. That’s got to be a win win, surely?